Excursion from Dorjiling to Great Rungeet — Zones of vegetation — Tree-ferns — Palms, upper limit of — Leebong, tea plantations — Ging — Boodhist remains — Tropical vegetation — Pines — Lepcha clearances — Forest fires — Boodhist monuments — Fig — Cane bridge and raft over Rungeet — Sago-palm — India-rubber — Yel Pote — Butterflies and other insects — Snakes — Camp — Temperature and humidity of atmosphere — Junction of Teesta and Rungeet — Return to Dorjiling — Tonglo, excursion to — Bamboo flowering — Oaks — Gordonia — Maize, hermaphrodite flowered — Figs — Nettles — Peepsa — Simonbong, cultivation at — European fruits at Dorjiling — Plains of India.

A very favourite and interesting excursion from Dorjiling is to the cane bridge over the Great Rungeet river, 6000 feet below the station. To this an excellent road has been cut, by which the whole descent of six miles, as the crow flies, is easily performed on pony-back; the road distance being only eleven miles. The scenery is, of course, of a totally different description from that of Sinchul, or even of the foot of the hills, being that of a deep mountain-valley. I several times made this trip; on the excursion about to be described, and in which I was accompanied by Mr. Barnes, I followed the Great Rungeet to the Teesta, into which it flows.

In descending from Dorjiling, the zones of vegetation are well marked between 6000 and 7000 feet by—1. The oak, chesnut, and Magnolias, the main features from 7000 to 10,000 feet.—2. Immediately below 6,500 feet, the tree-fern appears (Alsophila gigantea, Wall.), a widely-distributed

plant, common to the Himalaya, from Nepal eastward to the Malayan peninsula, Java, and Ceylon.—3. Of palms, a species of Calamus, and Plectocomia, the “Rhenoul” of the Lepchas. The latter, though not a very large plant, climbs lofty trees, and extends about 40 yards through the forest; 6,500 feet is the upper limit of palms in the Sikkim Himalaya, the Rhenoul alone attaining this elevation.*—4. The fourth striking feature is a wild plantain, which ascends to nearly the same elevation (“Lukhlo,” Lepcha). This is replaced by another, and rather larger species, at lower elevations; both ripen austere and small fruits, which are full of seeds, and quite uneatable; that commonly grown in Sikkim is an introduced stock (nor have the wild species ever been cultivated); it is very large, but poor in flavour, and does not bear seeds. The zones of these conspicuous plants are very clearly defined, and especially if the traveller, standing on one of the innumerable spurs which project from the Dorjiling ridge, cast his eyes up the gorges of green on either hand.

At 1000 feet below Dorjiling a fine wooded spur projects, called Leebong. This beautiful spot is fully ten degrees warmer than Mr. Hodgson’s house, and enjoys considerably more sunshine; peaches and English fruit-trees flourish extremely well, but do not ripen fruit. The tea-plant

* Four other Calami range between 1000 and 6000 feet on the outer hills, some of them being found forty miles distant from the plains of India. The other palms of Sikkim are, “Simong” (Caryota urens); it is rare, and ascends to nearly 5000 feet. Phœnix (probably P. acaulis, Buch.), a small, stemless species, which grows on the driest soil in the deep valleys; it is the “Schaap” of the Lepchas, who eat the young seeds, and use the feathery fronds as screens in hunting. Wallichia oblonjpgolia, the “Ooh” of the Lepchas, who make no use of it; Dr. Campbell and myself, however, found that it is an admirable fodder for horses, who prefer it to any other green food to be had in these mountains. Areca gracilis and Licuala peltata are the only other palms in Sikkim; but Cycas pectinata, with the India-rubber fig, occurs in the deepest and hottest valleys—the western limit of both these interesting plants. Of Pandanus there is a graceful species at elevations of 1000 to 4000 feet (“Borr,” Lepcha).

succeeds here admirably, and might be cultivated to great profit, and be of advantage in furthering a trade with Tibet. It has been tried on a large scale by Dr. Campbell at his residence (alt. 7000 feet), but the frosts and snow of that height injure it, as do the hailstorms in spring.

Below Leebong is the village of Ging, surrounded by steeps, cultivated with maize, rice, and millet. It is rendered very picturesque by a long row of tall poles, each bearing a narrow, vertically elongated banner, covered with Boodhist inscriptions, and surmounted by coronet-like ornaments, or spear-heads, rudely cut out of wood, or formed of basket-work, and adorned with cotton fringe. Ging is peopled by Bhotan emigrants, and when one dies, if his relations can afford to pay for them, two additional poles and flags are set up by the Lamas in honour of his memory, and that of Sunga, the third member of the Boodhist Trinity.

Below this the Gordonia commences, with Cedrela toona, and various tropical genera, such as abound near Punkabaree. The heat and hardness of the rocks cause the streams to dry up on these abrupt hills, especially on the eastern slope, and the water is therefore conveyed along the sides of the path, in conduits ingeniously made of bamboo, either split in half, or, what is better, whole, except at the septum, which is removed through a lateral hole. The oak and chesnut of this level (3000 feet), are both different from those which grow above, as are the brambles. The Arums are replaced by Caladiums. Tree-ferns cease below 4000 feet, and the large bamboo abounds.

At about 2000 feet, and ten miles distant from Dorjiling, we arrived at a low, long spur, dipping down to the bed of the Rungeet, at its junction with the Rungmo. This is close to the boundary of the British ground, and there is a

guard-house, and a sepoy or two at it; here we halted. It took the Lepchas about twenty minutes to construct a table and two bedsteads within our tent; each was made of four forked sticks, stuck in the ground, supporting as many side-pieces, across which were laid flat split pieces of bamboo, bound tightly together by strips of rattan palm-stem. The beds were afterwards softened by many layers of bamboo-leaf, and if not very downy, they were dry, and as firm as if put together with screws and joints. This spur rises out of a deep valley, quite surrounded by lofty mountains; it is narrow, and covered with red clay, which the natives chew as a cure for goître. North, it looks down into a gully, at the bottom of which the Rungeet’s foamy stream winds through a dense forest. In the opposite direction, the Rungmo comes tearing down from the top of Sinchul, 7000 feet above; and though its roar is heard, and its course is visible throughout its length, the stream itself is nowhere seen, so deep does it cut its channel. Except on this, and a few similarly hard rocky hills around, the vegetation is a mass of wood and jungle. At this spot it is rather scanty and dry, with abundance of the Pinus lonjpgolia and Sal. The dwarf date-palm (Phœnix acaulis) also, was very abundant.

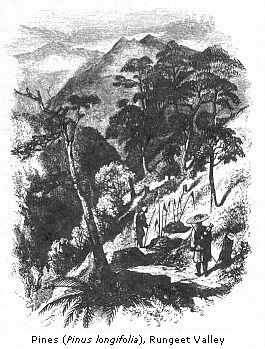

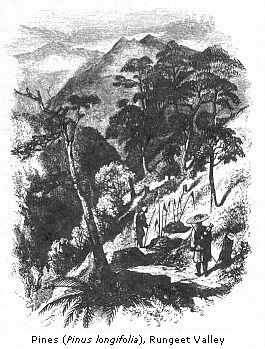

The descent to the river was exceedingly steep, the banks presenting an impenetrable jungle. The pines on the arid crests of the hills around formed a remarkable feature: they grow like the Scotch fir, the tall, red trunks springing from the steep and dry slopes. But little resin exudes from the stem, which, like that of most pines, is singularly free from lichens and mosses; its wood is excellent, and the charcoal of the burnt leaves is used as a pigment. Being confined to dry soil, this pine is local in Sikkim, and the elevation it attains here is not above 3000 feet. In Bhotan,

where there is more dry country, its range is about the same, and in the north-west Himalaya, from 2,500 to 7000 feet.

The Lepcha never inhabits one spot for more than three successive years, after which an increased rent is demanded by the Rajah. He therefore squats in any place which he can render profitable for that period, and then moves to another. His first operation, after selecting a site, is to burn the jungle; then he clears away the trees, and cultivates between the stumps. At this season, firing the jungle is a frequent practice, and the effect by night is exceedingly fine; a forest, so dry and full of bamboo, and extending over such steep hills, affording grand blazing spectacles. Heavy clouds canopy the mountains above, and, stretching across the valleys, shut out the firmament; the air is a dead calm, as usual in these deep gorges, and the fires, invisible by day, are seen raging all around, appearing to an inexperienced eye in all but dangerous proximity. The voices of birds and insects being hushed, nothing is audible but the harsh roar of the rivers, and occasionally, rising far above it, that of the forest fires. At night we were literally surrounded by them; some smouldering, like the shale-heaps at a colliery, others fitfully bursting forth, whilst others again stalked along with a steadily increasing and enlarging flame, shooting out great tongues of fire, which spared nothing as they advanced with irresistible might. Their triumph is in reaching a great bamboo clump, when the noise of the flames drowns that of the torrents, and as the great stem-joints, burst, from the expansion of the confined air, the report is as that of a salvo from a park of artillery. At Dorjiling the blaze is visible, and the deadened reports of the bamboos bursting is heard throughout the night; but in the valley, and within a mile of the scene of destruction, the effect is the

most grand, being heightened by the glare reflected from the masses of mist which hover above.

On the following morning we pursued a path to the bed of the river; passing a rude Booddhist monument, a pile of slate-rocks, with an attempt at the mystical hemisphere at top. A few flags or banners, and slabs of slate, were inscribed with “Om Mani Padmi om.” Placed on a jutting angle of the spur, backed with the pine-clad hills, and flanked by a torrent on either hand, the spot was wild and picturesque; and I could not but gaze with a feeling of deep interest on these emblems of a religion which perhaps numbers more votaries than any other on the face of the globe. Booddhism in some form is the predominating creed, from Siberia and Kamschatka to Ceylon, from the Caspian steppes to Japan, throughout China, Burmah, Ava, and a part of the Malayan Archipelago. Its associations enter into every book of travels over these vast regions, with Booddha, Dhurma, Sunga, Jos, Fo, and praying-wheels. The mind is arrested by the names, the imagination captivated by the symbols; and though I could not worship in the grove, it was impossible to deny to the inscribed stones such a tribute as is commanded by the first glimpse of objects which have long been familiar to our minds, but not previously offered to our senses. My head Lepcha went further: to a due observance of demon-worship he united a deep reverence for the Lamas, and he venerated their symbols rather as theirs than as those of their religion. He walked round the pile of stones three times from left to right repeating his “Om Mani,” etc., then stood before it with his head hung down and his long queue streaming behind, and concluded by a votive offering of three pine-cones. When done, he looked round at me, nodded, smirked, elevated the angles of his little

turned-up eyes, and seemed to think we were safe from all perils in the valleys yet to be explored.

In the gorge of the Rungeet the heat was intolerable, though the thermometer did not rise above 95°. The mountains leave but a narrow gorge between them, here and there bordered by a belt of strong soil, supporting a towering crop of long cane-like grasses and tall trees. The troubled river, about eighty yards across, rages along over a

gravelly bed. Crossing the Rungmo, where it falls into the Rungeet, we came upon a group of natives drinking fermented Murwa liquor, under a rock; I had a good deal of difficulty in getting my people past, and more in inducing one of the topers to take the place of a Ghorka (Nepalese) of our party who was ill with fever. Soon afterwards, at a most wild and beautiful spot, I saw, for the first time, one of the most characteristic of Himalayan objects of art, a cane bridge. All the spurs, round the bases of which the river flowed, were steep and rocky, their flanks clothed with the richest tropical forest, their crests tipped with pines. On the river’s edge, the Banana, Pandanus, and Bauhinia, were frequent, and Figs prevailed. One of the latter (of an exceedingly beautiful species) projected over the stream, growing out of a mass of rock, its roots interlaced and grasping at every available support, while its branches, loaded with deep glossy foliage, hung over the water.

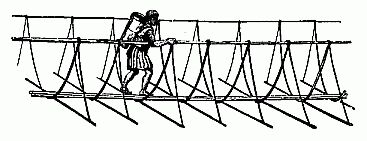

This tree formed one pier for the canes; that on the opposite bank, was constructed of strong piles, propped with large stones; and between them swung the bridge,* about eighty yards long, ever rocking over the torrent (forty feet below). The lightness and extreme simplicity of its structure were very remarkable. Two parallel canes, on the same horizontal plane, were stretched across the stream; from them others hung in loops, and along

* A sketch of one of these bridges will be found in Vol. II.

the loops were laid one or two bamboo stems for flooring; cross pieces below this flooring, hung from the two upper canes, which they thus served to keep apart. The traveller grasps one of the canes in either hand, and walks along the loose bamboos laid on the swinging loops: the motion is great, and the rattling of the loose dry bamboos is neither a musical sound, nor one calculated to inspire confidence; the whole structure seeming as if about to break down. With shoes it is not easy to walk; and even with bare feet it is often difficult, there being frequently but one bamboo, which, if the fastening is loose, tilts up, leaving the pedestrian suspended over the torrent by the slender canes. When properly and strongly made, with good fastenings, and a floor of bamboos laid transversely, these bridges are easy to cross. The canes are procured from a species of Calamus; they are as thick as the finger, and twenty, or thirty yards long, knotted together; and the other pieces are fastened to them by strips of the same plant. A Lepcha, carrying one hundred and forty pounds on his back, crosses without hesitation, slowly but steadily, and with perfect confidence.

A deep broad pool below the bridge was made available for a ferry: the boat was a triangular raft of bamboo stems, with a stage on the top, and it was secured on the opposite side of the stream, having a cane reaching across to that on which we were. A stout Lepcha leapt into the boiling flood, and boldly swam across, holding on by the cane, without which he would have been carried away. He unfastened the raft, and we drew it over by the cane, and, seated on the stage, up to our knees in water, we were pulled across; the raft bobbing up and down over the rippling stream.

We were beyond British ground, on the opposite bank,

where any one guiding Europeans is threatened with punishment: we had expected a guide to follow us, but his non-appearance caused us to delay for some hours; four roads, or rather forest paths, meeting here, all of which were difficult to find. After a while, part of a marriage-procession came up, headed by the bridegroom, a handsome young Lepcha, leading a cow for the marriage feast; and after talking to him a little, he volunteered to show us the path. On the flats by the stream grew the Sago palm (Cycas pectinata), with a stem ten feet high, and a beautiful crown of foliage; the contrast between this and the Scotch-looking pine (both growing with oaks and palms) was curious. Much of the forest had been burnt, and we traversed large blackened patches, where the heat was intense, and increased by the burning trunks of prostrate trees, which smoulder for months, and leave a heap of white ashes. The larger timber being hollow in the centre, a current of air is produced, which causes the interior to burn rapidly, till the sides fall in, and all is consumed. I was often startled, when walking in the forest, by the hot blast proceeding from such, which I had approached without a suspicion of their being other than cold dead trunks.

Leaving the forest, the path led along the river bank, and over the great masses of rock which strewed its course. The beautiful India-rubber fig was common, as was Bassia butyracea, the “Yel Pote” of the Lepchas, from the seeds of which they express a concrete oil, which is received and hardens in bamboo vessels. On the forest-skirts, Hoya, parasitical Orchideæ, and Ferns, abounded; the Chaulmoogra, whose fruit is used to intoxicate fish, was very common; as was an immense mulberry tree, that yields a milky juice and produces a long green sweet fruit. Large fish, chiefly

Cyprinoid, were abundant in the beautifully clear water of the river. But by far the most striking feature consisted in the amazing quantity of superb butterflies, large tropical swallow-tails, black, with scarlet or yellow eyes on their wings. They were seen everywhere, sailing majestically through the still hot air, or fluttering from one scorching rock to another, and especially loving to settle on the damp sand of the river-edge; where they sat by thousands, with erect wings, balancing themselves with a rocking motion, as their heavy sails inclined them to one side or the other; resembling a crowded fleet of yachts on a calm day. Such an entomological display cannot be surpassed. Cicindelæ were very numerous, and incredibly active, as were Grylli; and the great Cicadeæ were everywhere lighting on the ground, when they uttered a short sharp creaking sound, and anon disappeared, as if by magic. Beautiful whip-snakes were gleaming in the sun: they hold on by a few coils of the tail round a twig, the greater part of their body stretched out horizontally, occasionally retracting, and darting an unerring aim at some insect. The narrowness of the gorge, and the excessive steepness of the bounding hills, prevented any view, except of the opposite mountain face, which was one dense forest, in which the wild Banana was conspicuous.

Towards evening we arrived at another cane-bridge, still more dilapidated than the former, but similar in structure. For a few hundred yards before reaching it, we lost the path, and followed the precipitous face of slate-rocks overhanging the stream, which dashed with great violence below. Though we could not walk comfortably, even with our shoes off, the Lepchas, bearing their enormous loads, proceeded with perfect indifference.

Anxious to avoid sleeping at the bottom of the valley,

we crawled, very much fatigued, through burnt dry forest, up a very sharp ridge, so narrow that the tent sat astride on it, the ropes being fastened to the tops of small trees on either slope. The ground swarmed with black ants, which got into our tea, sugar, etc., while it was so covered with charcoal, that we were soon begrimed. Our Lepchas preferred remaining on the river-bank, whence they had to bring up water to us, in great bamboo “chungis,” as they are called. The great dryness of this face is owing to its southern exposure: the opposite mountains, equally high and steep, being clothed in a rich green forest.

At nine the next morning, the temperature was 78°, but a fine cool easterly wind blew. Descending to the bed of the river, the temperature was 84°. The difference in humidity of the two stations (with about 300 feet difference in height) was more remarkable; at the upper, the wet bulb thermometer was 67·5°, and consequently the saturation point, 0·713; at the lower, the wet bulb was 68°, and saturation, 0·599. The temperature of the river was, at all hours of the preceding day, and this morning, 67·5°.*

Our course down the river was by so rugged a path, that, giddy and footsore with leaping from rock to rock, we at last attempted the jungle, but it proved utterly impervious. On turning a bend of the stream, the mountains of Bhotan suddenly presented themselves, with the Teesta flowing at their base; and we emerged at the angle formed by the junction of the Rungeet, which we

* At this hour, the probable temperature at Dorjiling (6000 feet above this) would be 56°, with a temperature of wet bulb 55°, and the atmosphere loaded with vapour. At Calcutta, again, the temperature was at the observatory 98.·3°, wet bulb, 81.8°, and saturation=0·737. The dryness of the air, in the damper-looking and luxuriant river-bed, was owing to the heated rocks of its channel; while the humidity of the atmosphere over the drier-looking hill where we encamped, was due to the moisture of the wind then blowing.

had followed from the west, of the Teesta, coming from the north, and of their united streams flowing south.

We were not long before enjoying the water, when I was surprised to find that of the Teesta singularly cold; its temperature being 7° below that of the Rungeet.* At the salient angle (a rocky peninsula) of their junction, we could almost place one foot in the cold stream and the other in the warmer. There is a no less marked difference in the colour of the two rivers; the Teesta being sea-green and muddy, the Great Rungeet dark green and very clear; and the waters, like those of the Arve and Rhone at Geneva, preserve their colours for some hundred yards; the line separating the two being most distinctly drawn. The Teesta, or main stream, is much the broadest (about 80 or 100 yards wide at this season), the most rapid and deep. The rocks which skirt its bank were covered with a silt or mud deposit, which I nowhere observed along the Great Rungeet, and which, as well as its colour and coldness, was owing to the vast number of then melting glaciers drained by this river. The Rungeet, on the other hand, though it rises amongst the glaciers of Kinchinjunga and its sister peaks, is chiefly supplied by the rainfall of the outer ranges of Sinchul and Singalelah, and hence its waters are clear, except during the height of the rains.

From this place we returned to Dorjiling, arriving on the afternoon of the following day.

The most interesting trip to be made from Dorjiling, is that to the summit of Tonglo, a mountain on the Singalelah

* This is, no doubt, due partly to the Teesta flowing south, and thus having less of the sun, and partly to its draining snowy mountains throughout a much longer portion of its course. The temperature of the one was 67·5°, and that of the other 60·5°.

range, 10,079 feet high, due west of the station, and twelve miles in a straight line, but fully thirty by the path.*

Leaving the station by a native path, the latter plunges at once into a forest, and descends very rapidly, occasionally emerging on cleared spurs, where are fine crops of various millets, with much maize and rice. Of the latter grain as many as eight or ten varieties are cultivated, but seldom irrigated, which, owing to the dampness of the climate, is not necessary: the produce is often eighty-fold, but the grain is large, coarse, reddish, and rather gelatinous when boiled. After burning the timber, the top soil is very fertile for several seasons, abounding in humus, below which is a stratum of stiff clay, often of great thickness, produced by the disintegration of the rocks;† the clay makes excellent bricks, and often contains nearly 30 per cent. of alumina.

At about 4000 feet the great bamboo (“Pao” Lepcha) abounds; it flowers every year, which is not the case with all others of this genus, most of which flower profusely over large tracts of country, once in a great many years, and then die away; their place being supplied by seedlings, which grow with immense rapidity. This well-known fact is not due, as some suppose, to the life of the species being of such a duration, but to favourable circumstances in the season. The Pao attains a height of 40 to 60 feet, and the culms average in thickness the human thigh; it is used for large water-vessels, and its leaves form admirable thatch, in universal use for European houses at Dorjiling. Besides this, the Lepchas are acquainted with nearly a dozen kinds of bamboo; these occur at various elevations below 12,000

* A full account of the botanical features noticed

on this excursion (which I made in May, 1848, with Mr. Barnes) has

appeared in the “London Journal of Botany,” and the

“Horticultural Society’s Journal,” and I shall,

therefore, recapitulate its leading incidents only.

† An analysis of the soil will be found in the Appendix.

feet, forming, even in the pine-woods, and above their zone, in the skirts of the Rhododendron scrub, a small and sometimes almost impervious jungle. In an economical point of view they maybe classed as those which split readily, and those which do not. The young shoots of several are eaten, and the seeds of one are made into a fermented drink, and into bread in times of scarcity; but it would take many pages to describe the numerous purposes to which the various species are put.

Gordonia is their most common tree (G. Wallichii), much prized for ploughshares and other purposes requiring a hard wood: it is the “Sing-brang-kun ” of the Lepchas, and ascends to 4000 feet. Oaks at this elevation occur as solitary trees, of species different from those of Dorjiling. There are three or four with a cup-shaped involucre, and three with spinous involucres enclosing an eatable sweet nut; these generally grow on a dry clayey soil.

Some low steep spurs were well cultivated, though the angle of the field was upwards of 25°; the crops, chiefly maize, were just sprouting. This plant is occasionally hermaphrodite in Sikkim, the flowers forming a large drooping panicle and ripening small grains; it is, however, a rare occurrence, and the specimens are highly valued by the people.

The general prevalence of figs,* and their allies, the nettles,† is a remarkable feature in the botany of the Sikkim Himalaya, up to nearly 10,000 feet. Of the former there were here five species, some bearing eatable and very palatable fruit of enormous size, others with the fruit small and borne on prostrate, leafless branches, which spring from the root and creep along the ground.

A troublesome, dipterous insect (the “Peepsa,” a species of Siamulium) swarms on the banks of the streams; it is very small and black, floating like a speck before the eye; its bite leaves a spot of extravasated blood under the cuticle, very irritating if not opened.

Crossing the Little Rungeet river, we camped on the base of Tonglo. The night was calm and clear, with faint

* One species of this very tropical genus ascends

almost to 9000 feet on the outer ranges of Sikkim.

† Of two of these cloth is made, and of a third, cordage.

The tops of two are eaten, as are several species of

Procris. The “Poa” belongs to this order, yielding

that kind of grass cloth fibre, now abundantly imported into

England from the Malay Islands, and used extensively for

shirting.

cirrus, but no dew. A thermometer sunk two feet in rich vegetable mould stood at 78° two hours after it was lowered, and the same on the following morning. This probably indicates the mean temperature of the month at that spot, where, however, the dark colour of the exposed loose soil must raise the temperature considerably.

May 20th.—The temperature at sunrise was 67°; the morning bright, and clear over head, but the mountains looked threatening. Dorjiling, perched on a ridge 5000 feet above us, had a singular appearance. We ascended the Simonbong spur of Tonglo, so called from a small village and Lama temple of that name on its summit; where we arrived at noon, and passing some chaits* gained the Lama’s residence.

Two species of bamboo, the “Payong” and “Praong” of the Lepchas, here replace the Pao of the lower regions. The former was flowering abundantly, the whole of the culms (which were 20 feet high) being a diffuse panicle of inflorescence. The “Praong” bears a round head of flowers at the ends of the leafy branches. Wild strawberry, violet, geranium, etc., announced our approach to the temperate zone. Around the temple were potato crops and peach-trees, rice, millet, yam, brinjal (egg-apple), fennel, hemp (for smoking its narcotic leaves), and cummin, etc. The potato thrives extremely well as a summer crop, at 7000 feet, in Sikkim, though I think the root (from the Dorjiling stock) cultivated as a winter crop in the plains, is superior both in size and flavour. Peaches never ripen in this part of Sikkim, apparently from the want of sun; the tree

* The chait of Sikkim, borrowed from Tibet, is a square pedestal, surmounted with a hemisphere, the convex end downwards, and on it is placed a cone, with a crescent on the top. These are erected as tombs to Lamas, and as monuments to illustrious persons, and are venerated accordingly, the people always passing them from left to right, often repeating the invocation, “Ora Mani Padmi om.”

grows well at from 3000 to 7000 feet elevation, and flowers abundantly; the fruit making the nearest approach to maturity (according to the elevation) from July to October. At Dorjiling it follows the English seasons, flowering in March and fruiting in September, when the scarce reddened and still hard fruit falls from the tree. In the plains of India, both this and the plum ripen in May, but the fruits are very acid.

It is curious that throughout this temperate region, there is hardly an eatable fruit except the native walnut, and some brambles, of which the “yellow” and “ground raspberry” are the best, some insipid figs, and a very austere crab-apple. The European apple will scarcely ripen,* and the pear not at all. Currants and gooseberries show no disposition to thrive, and strawberries are the only fruits that ripen at all, which they do in the greatest abundance. Vines, figs, pomegranates, plums, apricots, etc., will not succeed even as trees. European vegetables again grow, and thrive remarkably well throughout the summer of Dorjiling, and the produce is very fair, sweet and good, but inferior in flavour to the English.

Of tropical fruits cultivated below 4000 feet, oranges and indifferent bananas alone are frequent, with lemons of various kinds. The season for these is, however, very short; though that of the plantain might with care be prolonged; oranges abound in winter, and are excellent, but neither so large nor free of white pulp as those of the Khasia hills, the West Indies, or the west coast of Africa. Mangos are brought from the plains, for though wild in Sikkim, the cultivated kinds do not thrive; I have

* This fruit, and several others, ripen at Katmandoo, in Nepal (alt. 4000 feet), which place enjoys more sunshine than Sikkim. I have, however, received very differedt accounts of the produce, which, on the whole, appears to be inferior.

seen the pine-apple plant, but I never met with good fruit on it.

A singular and almost total absence of the light, and of the direct rays of the sun in the ripening season, is the cause of this dearth of fruit. Both the farmer and orchard gardener in England know full well the value of a bright sky as well as of a warm autumnal atmosphere. Without this corn does not ripen, and fruit-trees are blighted. The winter of the plains of India being more analogous in its distribution of moisture and heat to a European summer, such fruits as the peach, vine, and even plum, fig, strawberry, etc., may be brought to bear well in March, April, and May, if they are only carefully tended through the previous hot and damp season, which is, in respect to the functions of flowering and fruiting, their winter.

Hence it appears that, though some English fruits will turn the winter solstice of Bengal (November to May) into summer, and then flower and fruit, neither these nor others will thrive in the summer of 7000 feet on the Sikkim Himalaya, (though its temperature so nearly approaches that of England,) on account of its rain and fogs. Further, they are often exposed to a winter’s cold equal to the average of that of London, the snow lying for a week on the ground, and the thermometer descending to 25°. It is true that in no case is the extreme of cold so great here as in England, but it is sufficient to check vegetation, and to prevent fruit-trees from flowering till they are fruiting in the plains. There is in this respect a great difference between the climate of the central and eastern and western Himalaya, at equal elevations. In the western (Kumaon, etc.) the winters are colder than in Sikkim—the summers warmer and less humid. The rainy season is shorter, and

the sun shines so much more frequently between the heavy showers, that the apple and other fruits are brought to a much better state. It is true that the rain-gauge may show as great a fall there, but this is no measure of the humidity of the atmosphere, and still less so of the amount of the sun’s direct light and heat intercepted by aqueous vapour, for it takes no account of the quantity of moisture suspended in the air, nor of the depositions from fogs, which are far more fatal to the perfecting of fruits than the heaviest brief showers. The Indian climate, which is marked by one season of excessive humidity and the other of excessive drought, can never be favourable to the production either of good European or tropical fruits. Hence there is not one of the latter peculiar to the country, and perhaps but one which arrives at full perfection; namely, the mango. Tile plantains, oranges, and pine-apples are less abundant, of inferior kinds, and remain a shorter season in perfection than they do in South America, the West Indies, or Western Africa.